Who is The Most Vulnerable?: Conceptualising Vulnerability in Anticipatory Action

Media

Image

While the costs of prevention have to be paid in the present, its benefits lie in a distant future

Kofi Annan, Previous United Nations Secretary-General (United Nations, 1999)

Blog content

Beatrice Phillips

Forecast-based Action (FbA), a mechanism of the wider anticipatory action movement, is a programme that enables access to humanitarian funding for early action based on forecast information and risk analysis with the goal to anticipate disasters prevent their impact and reduce human suffering and losses IFRC and German Red Cross FbA was developed to address the gap in the humanitarian funding landscape which does not take advantage of the window of time that exists after the issuance of science-based early warnings but before a disaster materialises (Coughlan de Perez et al., 2015, p. 896). The recent attention garnered by FbA demonstrates a potential avenue for growth in disaster response. To receive future funding, the assurance of programme effectiveness is required. In this assurance, it is necessary to understand who is being helped and why, or in other words, the most vulnerable. For my research, I focused on the cold waves and snowfall FbA programme in Peru due its status as the first FbA programme on any hazard approved by the Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Centre (Climate Centre) and the availability of supporting documents.

Approaches to Vulnerability and the Role of Anthropology

If one checks the about pages of many non-profits, NGOs, and multi-lateral institutions, the term 'vulnerable' or the phrase 'the most vulnerable' often appears. The frequency of this terminology prompted me to question who was defining the most vulnerable and how this process was framing the selected beneficiaries in a project or programme.

See these NGO about pages here:

-

Borderless: https://www.borderlessngo.org/about-us

-

Relief International: https://www.ri.org/about-us/

In academia, the general agreement on defining vulnerability is that the term is a buzzword, meaning its numerous definitions are contested and lack a uniform understanding (Birkmann, 2006). Several broader approaches to vulnerability have developed which I utilised to help navigate this murkiness in my research. In relation to hazards (necessary in my research due to the hazard-centric focus of anticipatory action), the hazards-of-place approach, centred on the socio-economic characteristics of group within a specific location through selection of quantitative indicators (Oulahen et al. 2018, p.2493), and political ecology approach, centred on the ways in which social, economic and other factors can overlap to heighten the effects of a hazard (Wisner et al. 2004, p.176), gained traction as key methods to define vulnerability in a setting.

While there exists a plethora of studies on the conceptualisation of vulnerability across institutions, within programmes, and in communities, there is a lack of multi-level, qualitative examination of the conceptualisation of the term (Segnestam et al. 2006, p. 13; Camponeschi, 2021, p. 85). The intimate nature of determining who is truly the most vulnerable led my research to take an anthropological lens (Lessard, Caine, and Clandinin, 2018, p. 203), and interview key stakeholders at the programme and institutional level, and utilise previously obtained qualitative data at the community level (Cruz Roja Peruana, 2016a; Cruz Roja Peruana, 2016b; Cruz Roja Peruana, 2016c).

Stakeholders' Understanding of Vulnerability

Out of the thirteen participants interviewed for my research, who were all connected to FbA in the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), each conceptualised vulnerability in varying manners reliant on different elements and indicators. However, due to the focus of FbA, all participants acknowledged a common theme: that vulnerability to them was reflective of the hazard, or the risk stemming from a specific hazard, in a limited geographic area.

"It's a risk-based approach we have you're always vulnerable to something" (Participant 10, Interview, June 2021)

Remarkably, most participants remained highly critical of their conceptualisations of vulnerability, admitting it is context specific and should be community driven.

"We need to try to understand what vulnerability means in the respective context we are bound" (Participant 1, Interview, May 2021)

"Does the definition of vulnerability reflect the reality in any community at any one point in time?" (Participant 8, Interview, June 2021)

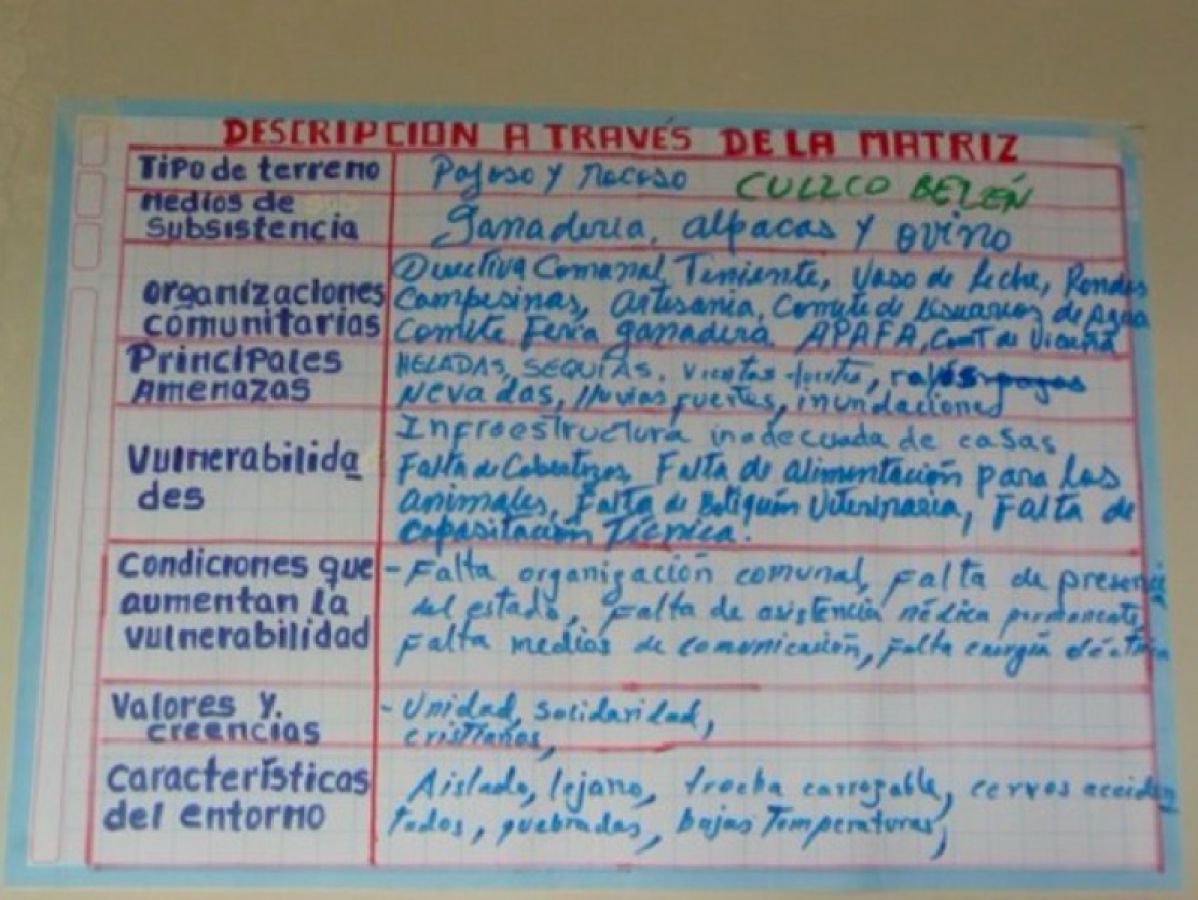

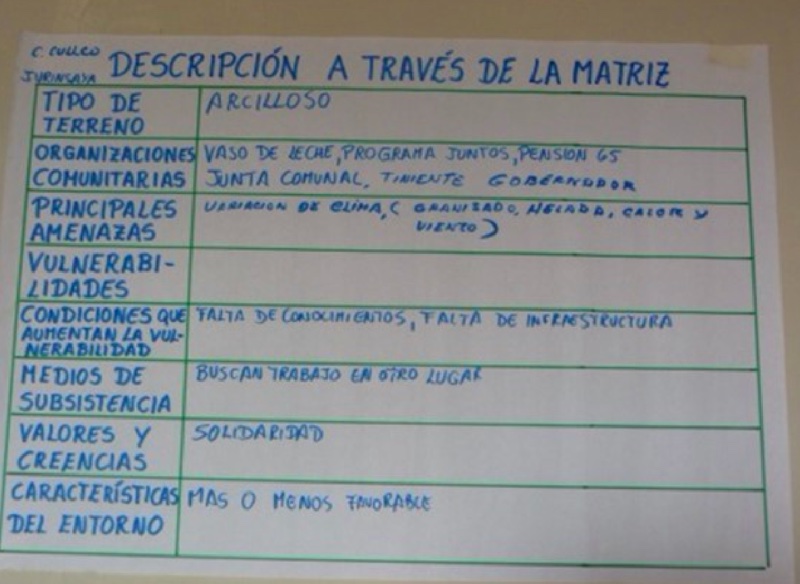

To the right are two images taken from Vulnerability and Capacity Assessment workshops with the Peruvian Red Cross in the Cullco Jurinsaya community (top) and Cullco Bién community (bottom). These tables, illustrating the threats and vulnerabilities the community faces, were prepared by local participants alongside the Peruvian Red Cross. The challenge of accessing communities highlights the importance of National Societies in leading FbA, or other mechanisms of anticipatory action, in each country. If the conceptualisation of vulnerability, and the reflective FbA programme, is to be community-driven, it is crucial that steps are taken (as they currently are by the Climate Centre and National Societies of the IFRC) to ensure the community is involved in all phases.

Moving Forward

"We can't respond to, or provide a service to everyone. We want to do that but we can't do that because we don't have the capacity" (Participant 7, Interview, June 2021)

Participant 7 acknowledges a caveat with FbA, as well as other anticipatory action formats. Its success in responding local needs is due to its targeted nature. An FbA programme focuses on just one hazard, or in the case of the snowfall and cold waves programme, two inextricably linked hazards. As most countries are threatened by several varying hazards, limited capacity of organisational support poses the challenge of deciding who is the most vulnerable to one specific hazard. The time and effort it takes to make such a decision has so far proved successful in the preliminary efforts of FbA and other anticipatory action programmes, but it still leaves the ethical questions of prioritising some lives over others.

While FbA wholeheartedly sits in the humanitarian field, its capability for both rapid humanitarian action and long-term preparation offers lessons to other programmes in the humanitarian field, development field, and governments. Through identifying and examining vulnerability in a FbA, or an anticipatory action programme, my research illustrates a reflective method to contemplate the implications of two key aspects of colonial and post- colonial narratives of humanitarianism and development: how narratives influence organisations' identification of beneficiaries and how these narratives are prompting organisations to utilise participatory methods to ensure those most vulnerable have a say in what support they receive and how. While the use of participatory methods in the development field has arguably become common place (McEwan, 2008, 266), their use in humanitarian response is not as frequent (Ormel et al, 2020, 1). This is partly due to the practical nature that humanitarian response, typically framed in discourse as an emergency (Calhoun, 2010, 32), often lacks the time to go through the extensive process of inclusive involvement (Calhoun, 2004, 376).

FbA is making strides to overcome colonial narratives by localizing action in response to a fluidly defined group of the most vulnerable (Tozier de la Poterie et al, 2019, 165). While indicators of vulnerability are preselected in direct cooperation with communities, the specific target beneficiaries are not defined until a hazard has been forecasted (Peruvian Red Cross et al, 2018, 10), removing the potential for colonial narratives to influence major decision making regards beneficiaries (McEwan, 2008, 232). By operating through National Societies, who typically have extensive experience in disaster response in their respective countries, vulnerable communities are both pre-emptively identified and assisted in selecting the most effective methods of pre-emptive response (Peruvian Red Cross et al, 2018, 65- 66). This set-up is far from the typical colonial development implementation or humanitarian response in the 20th century, focused on outside intervention and limited involvement of beneficiaries (McEwan, 2008, 43-44).

As the anticipatory action movement takes hold, there is potential for a slide away from the community level in an effort to address a wider reach of beneficiaries. Continued integration of an anthropological lens in programme design and implementation, as well as monitoring and evaluation, is key if stakeholders across the institutional, programmatic and community levels wish anticipatory action to remain locally driven.

Sources

Birkmann, J. (2006) Measuring vulnerability to natural hazards: towards disaster resilient societies. United Nations University Press.

Calhoun C (2004) A world of emergencies fear intervention and the limits of cosmopolitan order. The Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology, vol. 41, no. 4, 373-395.

Calhoun C (2010) The idea of emergency humanitarian action and global disorder. In Fassin, D. and Pandolfi, M. (Eds.) Contemporary States of Emergency: the Politics of Military and Humanitarian Interventions (New York: Zone Books).

Camponeschi, C. (2021) 'Narratives of vulnerability and resilience: an investigation of the climate action plans of New York City and Copenhagen', Geogorum, 123, pp. 78-88.

Coughlan de Perez, E., van den Hurk, B., van Aalst, M. K., Jongman, B., Klose, T. and Suarez, P. (2015) 'Forecast-based financing: an approach for catalyzing humanitarian action based on extreme weather and climate forecasts', Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, 15(4), pp. 895-904.

Cruz Roja Peruana (2016a) Comunidad de Cullco Beln, Cullco Jurinsaya y Llaulli, Districto de Potoni, Provincia de Azngaro - Puno: Analisis de vulnerabilidades y capacidades [Internal Document].

Cruz Roja Peruana (2016b) Comunidad de Ticani y Santa Ana de Tarucani, Distrito de Quilcapuncu y Putina, Provincia de San Antonio de Putina - Puno: Analisis de vulnerabilidades y capacidades [Internal Document].

Cruz Roja Peruana (2016c) Comunidad Ordua, Distrito de Santa Luca, Provincia de Lampa - Puno: analisis de vulnerabilidades y capacidades [Internal Document].

IFRC and German Red Cross (2021b) What is Forecast-based Financing? Available at: https://www.forecast-based-financing.org/about/ (Accessed: 20 March 2021).

Lessard, S., Caine, V. and Clandinin, D. J. (2018) 'Exploring neglected narratives: understanding vulnerability in narrative inquiry', Irish Educational Studies, 37(2), pp. 191- 204.

McEwan, C. (2008) Postcolonialism and development. London: Routledge.

Ormel, I, Salsberg, J., Hunt, M., Doucet, A. Hinton, L., Macaulay, A. C., and Law, S. (2020) Key issues for participatory research in the design and implementation of humanitarian assistance a scoping review Global Health Action, vol. 13, 1-14.

Oulahen, G., Chang, S. E., Yip, J. Z. K., Conger, T., Marteleira, M. and Carter, C. (2018) 'Contextualizing institutional factors in an indicator-based analysis of hazard vulnerability for coastal communities', Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 61(14), pp. 2491-2511.

Peruvian Red Cross, German Red Cross, Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Centre and German Humanitarian Assistance (2018) Early action plan: cold waves and snowfalls [Internal Document].

Segnestam, L., Simonsson, L., Rubiano, J. and Morales, M. (2006) Cross-level institutional processes and vulnerability to natural hazards in Hondorus. Stockholm: Stockholm Environmental Institute.

Tozier de la Poterie, A., Clatworthy, Y., Easton-Calabria, E., Coughlan de Perez, E., Lux, S. and van Aalst, M. K. (2021) 'Managing multiple hazards: lessons from anticipatory humanitarian action for climate disasters during COVID-19', Climate and Development, ahead-of-print, pp. 1-15.

Wisner, B., Blaikie, P., Cannon, T. and Davis, I. (2004) At risk second edition: natural hazards, peoples vulnerability and disasters London: Routledge.

United Nations. Annual Report of the Secretary-General on the Work of the Organization of United Nations. Document A/54/1. New York: United Nations, 1999.